Fame

"If they've really got what it takes, it's going to take everything they've got."

(1980)

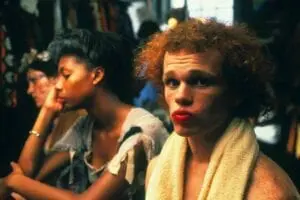

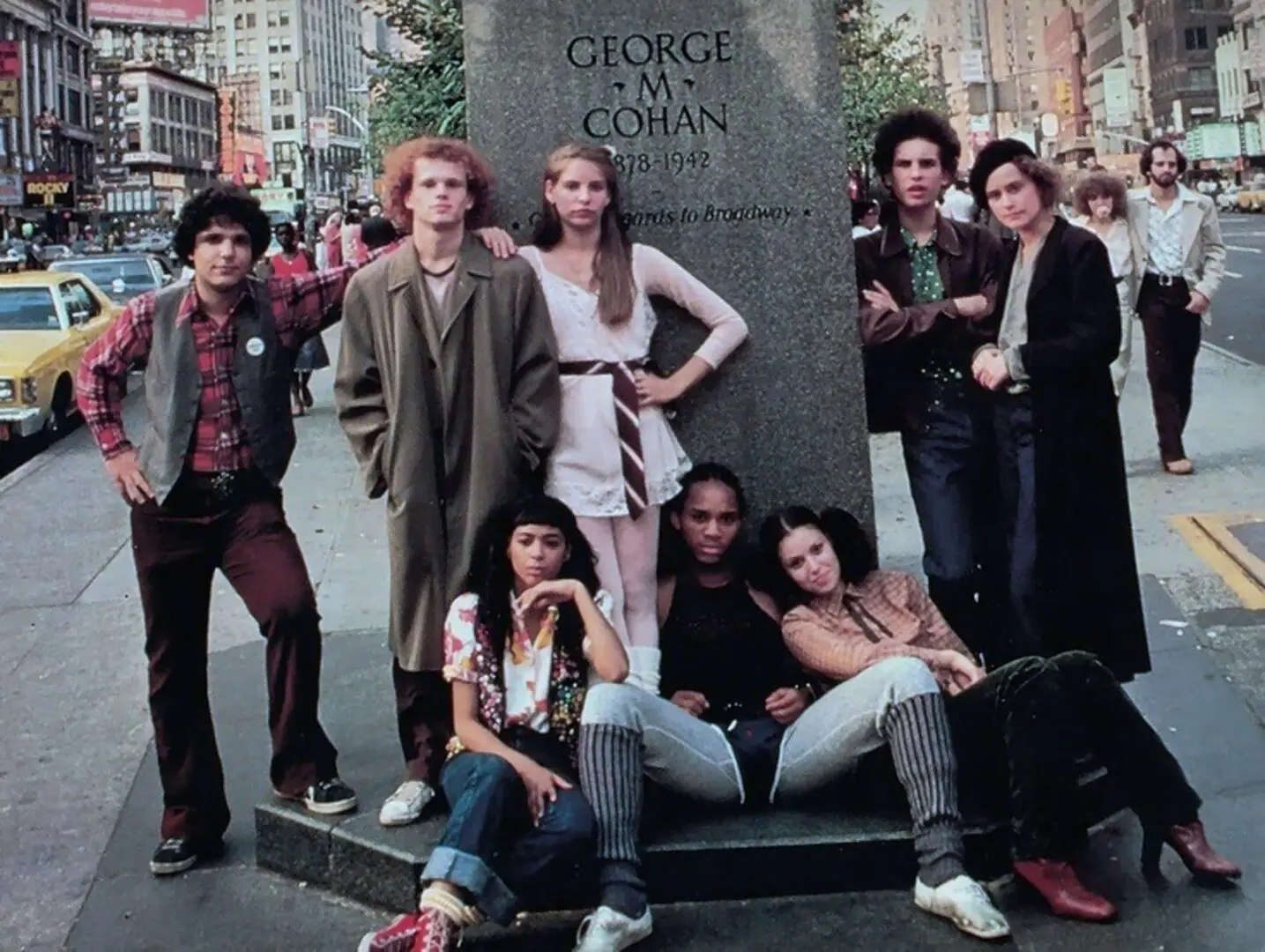

starring Paul McCrane, Irene Cara, Barry Miller, Maureen Teefy, Lee Curreri, Laura Dean and Gene Anthony Ray

PODCAST:

'80s Movies: A Guide to What's Wrong with Your Parents -

How FAME Influenced a Generation to Follow Their Dreams...and the Next Generation...and the Next...

Seven students go through four years at New York's High School of the Performing Arts and learn the amount of sweat and dedication required to follow their dreams.

Why it’s rad:

Fame is a musical. Let that sink in. It doesn’t feel like a musical because the singing and choreography occur so naturally, the music feels like an evolution of story and character rather than stopping the action to break into song.

Fame was rather groundbreaking when it came to representation. Hollywood is new to realizing the importance of representation and how seeing someone like yourself can make a person in the audience feel a lot less alone and a lot more empowered. Here are some examples:

- Montgomery McNeil was an out, gay character. A gay character in a major Hollywood film was a rarity, practically unheard of. McNeil accepted his homosexuality, and came out to his class even when his friend worried about the consequences. He endured some teasing, but his self-acceptance made the bully realize his efforts were a waste of time. Respecting Montgomery's acceptance of his identity, Ralph eventually makes Montgomery into his best friend.

- The film covers the spectrum of ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and economic disparity. Lead characters and background players display a variety of race across all classes, uniting them with common purpose as they pursue individual paths.

- An interracial relationship. As we said in the '80s, Leroy was "fi-i-i-i-ne." And, when he and rich bitch Hilary get together, it COULD be to get back at her parents, but when we see her crying to the nurse about having to abort their baby in pursuit of her career, it seems that it's more than that. A black and white couple was a rarity on screen in 1980.

So '80s:

Legwarmers. Fame turned the dancer's tool as a fashion accessory.

Dance Movies. Fame was inspired by the Broadway musical, A Chorus Line. Saturday Night Fever in 1977 gave renewed interest in dance. Grease in 1978 is credited with bringing back the musical. Then, All That Jazz (1979) brought in interest to the behind the scenes of New York Broadway performers. Fame came in as an early player in the ‘80s trend of dance films that included Flashdance (1983), Footloose (1984, from Fame lyricist Dean Pitchford), Breakin’ and Breakin’ 2: Electric Bugaloo (both released in 1984), White Nights (1985), A Chorus Line movie (1985), Dirty Dancing (1987). This extended into music and TV. "Solid Gold" – a countdown of the top 10 songs as danced by the scantily clad, sexy dancers – was a huge hit that debuted in the fall of 1980. Of course, music videos surged after the introduction of MTV in 1981 – and within a year or so, music acts began putting effort into these music videos with choreographed dance numbers. Even Michael Jackson stepped up his game – the difference between 1979’s "Don’t Stop Til You Get Enough" and 1983’s "Billie Jean," "Beat It," and "Thriller" is significant.

Historical Perspective

Fame isn’t about chasing fame. It’s about pursuit of craft. That’s not what anyone took away from the film. If you examine closer, the film doesn’t allude to anyone making it – especially not hot shot senior Michael, who threw away a college scholarship to go to Los Angeles and returns home, waiting tables. Over 40 years, this has changed significantly: kids just want to be famous. And, the days of tireless work because of passion have disappeared with the advent of reality show, YouTube and social media fame.

The year 1980 was a deeply cynical time. If 1980 was anything, it was a time when youth distrusted all authority. The hostility was well-deserved, as Americans learned their president was a crook, million of American boys were forced to fight and lost their lives in a war the government knew was unwinnable, and prejudice was at large in avenues like finding work and housing. The anger is evident in Ralph Garcy, an aspiring comedian who learned from his idol Freddie Prinze that to succeed, he’d need to hide his Puerto Rican roots. Garcy was played by Barry Miller, who pointed out how the cynicism was apparent in the original while he spoke out against the Fame remake in 2009 in a blog post: “Obamasized, Twitterized, and Homogenized into it’s safe PG-13 demographic, there will be no lines of dialogue accusing God of being an idiot or Santa Claus of being a thief, no tears of rage about the horrors perpetrated on a child because of the consuming evils of poverty and malevolent parental jealousy, no crucifix flung in the face of a priest, no angry monologue about trying to come to terms with the violent suicide of a Hollywood star, no snuffing out of potential through the self-destruction that lurks at the heart of the American Dream.”

What’s your damage?

Dreams don’t come easily. A far cry from today’s "if you can think it, you can BE it!” mentality, the ‘70s and ‘80s lived in a harsher world without magical thinking. Dreams can come true, but you will have to work for it – much harder than any other “less fun” endeavor.

Hard work, brutal feedback. As any cranky Boomer will tell you, they didn’t used to give out trophies for participation. Lisa is tossed from the dance department for not working hard enough and for not having the talent, it’s a shock to the system NOW. In 1980, teens were like, yeah – that’s realistic.

But what I hear you saying is that fame is POSSIBLE. While the movie didn’t show anyone actually succeeding, the film awakened young viewers to think a career in the arts was a choice (something parents of this era generally eschewed).

Peepholes. Again, with the peepholes. From Animal House to Porky's to Monster Squad, films of the late '70s and '80s were full of Peeping Toms. Even in Fame -- an Academy Award-nominated film with a bunch of gay guys, even then they felt it necessary to sexually infringe on the female dancers by creating comedy out of boys looking in at the girl characters while changing -- of course, including some shots of naked breasts. This continued to encourage a "boys will be boys" acceptance of bad behavior -- even though earlier, Coco mentions how she appreciates attending PA because unlike other public high schools, she doesn't have to worry about being raped in the hallway.

Leroy grabs girl's butts as he passes them in the hallway. With no consequence. Young women in the '80s can testify that this was not unusual -- guys thought they were slick and clever to slide their hands across a female's tush as they passed her. It's doubtful this was a scripted act and more likely an act from Gene Anthony Ray, who is reported on at least one occasion of "copping a feel." The Kinser Report relays Debbie Allen's stating an interview that during the filming of the TV series, Ray had "grabbed her ass while she was singing. After she scolded him, he was so hurt that he destroyed a dressing room." While the behavior may have passed on set as typical Leroy, it presented to young audiences that it was cool to touch girls without consent and that girls didn't mind or even felt appreciated by the lecherous act.

Behind the Scenes

ORIGINS

A song in A Chorus Line inspired the film. New York theatrical agent David De Silva was struck by a line in the song “Nothing” that mentions the High School of the Performing Arts. According to director Alan Parker, the song “alluded to acting classes where, unlike the other kids, the character Morales doesn’t quite ‘feel the motion’ of a bobsled in the snow — understandable being as she is from San Juan; and so she feels ”nothing,” which becomes her mantra and nickname.”

Playwright Christopher Gore was hired to write a screenplay. De Silva traveled to Florida to meet with Gore. The playwright and musician was behind the notorious Broadway sci-fi rock musical flop “Via Galactica” (1972) (at the time, Broadway’s biggest “financial disaster”) and wrote the books and lyrics for a musical Nefertiti (1977), about the noted Egyptian queen. Gore was paid $5,000.

Gore got to know the real students of the LaGuardia High School of the Performing Arts. Gore traveled to New York City and spent months at the school, interviewing students, to understand the life of the teens at "PA," as the school is called.

Hot Lunch was the original title. After MGM had greenlit the project, the filmmakers became aware that the term was also New York slang for oral sex so the search was on for a new title. Worse, during filming, a new porno was being released and ads were everywhere (back then, "adult films" were in theaters). It’s title? Hot Lunch. And, to the director’s chagrin, he learned a popular porn actor of the era was named Al Parker. A search for a new name was on.

Alan Parker was a hot director at the moment. Parker was part of the British invasion led by David Puttnam to bring British filmmakers into Hollywood. He directed the kids-as-gangster comedy Bugsy Malone (1976) but followed up with the serious, well-respected Midnight Express (1978) from then up-and-coming screenwriter Oliver Stone.

Parker and producing partner Alan Marshall read the script in Barney’s Beanery. The two were killing time waiting for a meeting nearby and read Gore’s script in the famed pub – as well as the script for One From the Heart. That script was later made into a film by Francis Ford Coppola.

The script needed work, but Parker sparked to the concept. Parker wrote on his website that Gore’s script “was by far the cruder of the two but I was attracted to the flip side of the American Dream; the eight main characters and particularly the eccentric milieu of this curious school, which at the time I never even knew existed. Also I always wanted to make a film in New York.”

David De Silva cried when Parker told him he wanted to rewrite the script. And not in a good way. De Silva was devastated that the script he’d overseen by Gore wasn’t up to snuff in the director’s estimation. The two agreed that Parker could rewrite the script, but he had to give Gore sole writing credit.

A serious tonal difference was struck. Gore and De Silva’s script was light and humorous. Parker saw a more serious take, as he put it: “a fusion of observation and fiction: a hard look at a subject which had traditionally been over glamorized.” Parker recrafted the script his way. This would be a point of contention throughout the entire filmmaking process.

Brit Alan Parker moved his family to Greenwich, Conn., and spent his days at PA, researching the students. “Director Alan Parker hung around PA for research, he observed lunchroom chaos with students spending their off-time working on their craft – and this is where he got most of the script: “The lunch-room at PA was my favorite place to hang out, talk and listen to the kids: their lives a littany of humiliation and rejection at cattle calls; their healing cruciate ligaments, calloused finger pads, latest crushes and impending nervous breakdowns. It was quite common to sit opposite a kid playing a cello, next to a dancer with her leg behind her ear, with another kid jamming on the piano in the corner while half a dozen erstwhile Stanley Kowalski’s belted out their lines to imaginary Blanches. All of this went into the script.”

MUSIC

Michael Gore was hired as music supervisor. Named “music coordinator,” the classical musician had written and played piano on his sister Lesley Gore’s 1950’s hit “It’s My Party.” He was to score and write the original songs for the film.

Dean Pitchford was brought in to co-write the lyrics. At the time, Pitchford was best known as a Broadway and Cabaret performer. He’d written music for Peter Allen’s Broadway show, “Up at One.” Michael Gore was in the audience opening night and immediately tracked Pitchford down. Gore asked Pitchford to collaborate.

Gore and Pitchford wrote songs overnight. Pitchford wrote on this website, “Michael and I wrote something like 13 songs while Fame was in production,” Dean remembers. “As the script pages came in, if there was any hint of a musical number – if it said anything like, ‘In the background, a group of kids sing and dance,’ for instance – Michael would call, and we’d work through the night to have something to play for the director Alan Parker the next day.”

The collaboration resulted in three "Fame"-ous songs. “The Body Electric,” “Red Light,” and the title song, “Fame,” which became a hit song for Irene Cara.

The single "Fame" drew its most striking line from a famous poem. Dean Pitchford said in high school, he’d used a speech from a British play about poet Dylan Thomas. Thomas is responding to a question asking why he’s spending his life writing poems, and he says, “Because in your poems, you get to live forever.” The line stuck with Pitchford – he said “it became a part of my psyche” – and he recycled it for the film’s title song.

Parker hated the song "Fame" the first time he heard it. Michael Gore played the theme song for the director at Haaren High and it was not music to Parker's ears. "As brilliant a musician and pianist as Michael is, his singing voice is more Noel Coward than Otis Redding and I consequently thought the new song was pretty awful. 'I’m gonna live forever, baby remember my name' he shouted with gusto. Oh boy, I thought. Who would listen to that?" he remembered on his site. Gore convinced him to let Cara lay down some tracks before he kiboshed it -- and the rest is history.

The title "Out Here On My Own" popped into Lesley Gore's head when her brother hummed the melody. Siblings Michael and Lesley Gore are longtime collaborators, back to when they were kids and they wrote "It's My Party (and I'll Cry if I Want To)" together and turned Lesley into a teen music sensation. Michael played the song for her on his living room piano and was humming along to it and Lesley told InDepth InterView in 2010 that the title immediately came to her. "I said to him, 'You know, give me a couple of days on that. Let me see if I can write that,' and I had read the script, so I sort of knew what we had to say."

"I Sing the Body Electric" was inspired by ELO meets Walt Whitman. While redrafting the script, Parker listened to Electric Light Orchestra's Eldorado over and over again. He encouraged Gore to use that song as inspiration while also giving him his vision: the song was to be performed by an orchestra, a rock band, a gospel choir, some solo singers, and have a dance break. Gore took the title from Whitman's "Leaves of Grass" poems.

Irene Cara contributed quite a bit ot the music production without credit. “I brought a lot of New York’s greatest session singers to Michael. He didn’t know Luther Vandross. I did. He didn’t know about Vicki Sue Robinson. I did,” Cara told Shondaland.com. “Michael wasn’t in with all the badass session players and singers that I knew. I never got any money for it. Never got acknowledged. I wrote 'Hot Lunch' to this very cool baseline that he came up with – that was the whole damn song.”

DANCING

Louis Falco was hired as choreographer. The dancer had his own company, The Louis Falco Repertory. He was known for reinventing modern dance. "The wonderful thing about the effortlessly creative and anarchic Louis, was his flexibility and lack of preciousness about his work," Parker wrote.

The dancers rehearsed for six weeks – but it was an unusual type of choreography. “Unlike the old MGM masters, or more recent masters like Bob Fosse for that matter, we didn’talways choreograph the camera movements for the numbers,” Parker said. “We’d been blessed with a wonderful group of kids and I didn’t want to inhibit them, or lose their spirit, by making them hit marks. I wanted it to appear that no outside hands were at work to hinder the naturalism."

In fact, the choreography and the way it was filmed was completely unique. TCM.com analyzed it like this:

The style of the film also marked a change from the past by presenting its musical numbers in quick cuts with multiple angles and crowded, kinetic frames, an approach that would soon become common in the burgeoning music video form of the 1980s. Fame may not be as visually splintered and rhythmically hyper as recent musicals by Baz Luhrmann (Moulin Rouge!, 2001) and Rob Marshall (Chicago, 2002; Nine, 2009) or the hot trend of dance films like Save the Last Dance (2001) and Step Up (2006), but it's a significant step away from Fred Astaire's insistence on being filmed in long, fluid takes that basked in the joy and wonder of a skilled body in continuous motion. Today, dance numbers seem to be created primarily in the editing room, a cacophony of extreme close-ups on flailing limbs and spinning heads, often begging the question of whether the performers are really dancers at all. The beginnings of that style are already evident here, but to its credit, Fame at least gives its cast plenty of chances to display their considerable talents and training. This was also one of the first films to use digital audio recording for its soundtrack.

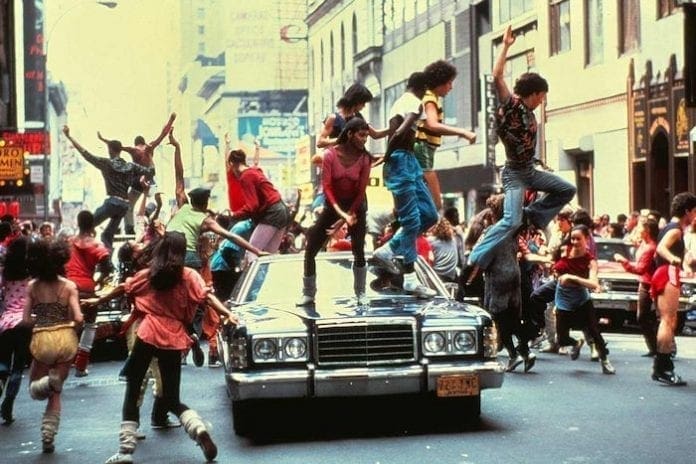

What won't be a surprise to you is that the "Fame" street dance create the biggest filming challenge. "Louis had choreographed eight different routines which he allocated amongst his dancers. We then randomly sprinkled the fifty dancers among 150 regular kids — the non-dancers — to raise the quality of the bedlam and achieve the choreographed chaos we were after," Parker wrote. "Certainly we were pushing reality to the extreme in that it doesn’t normally happen, but on the other hand there was always the chance that it could happen.

AUTHENTIC

Auditions are a smorgasbord of humanity. In 1982, Parade Magazine ran a story looking at the real High School of Performing Arts and revealed that around 4,500 hopefuls show up for auditions – and only 200 get in.

The school is a true ethnic melting pot. True to the film, the school is ethnically balanced. “This is a school where black kids, white kids, Puerto Rican kids, yellow kids, and all the others come together to be liberated,” Jerry Eskow, chairman of the drama department said. “In a real sense, they are all breaking out of their individual ghettos.”

Freddie Prinze did attend the LaGuardia High School of the Performing Arts. He didn’t graduate. At the time, alumni included Al Pacino, Liza Minelli, singer Melissa Manchester, Broadway star Ben Vereen.

School’s philosophical approach is accurate. “Most schools see a student as an empty vessel to fill with knowledge,” Eskow told Parade. “We believe that these kids are the reverse. You go to a medical school and come out a doctor. Here, the actor or dancer or musician already exists, and our job is to peel away the layers preventing that professional from emerging.”

INAUTHENTIC

Leroy’s special treatment. It’s hard to believe that Leroy could throw a destructive tantrum and not be kicked out of the school. It’s also hard to believe that given his continued issues with English teacher Mrs. Sherwood throughout his four years, that he’d be allowed to move forward. Go with your gut. “There’s just no kind of favoritism like that,” said Corinth Booker, a black dancing student at P.A. “Leroy gets away with being very stubborn and selfish, and he argues with teachers – like, ‘Are you telling me what I should do?’ That’s not the way it is.” In fact, Gene Anthony Ray was well aware of that fact: he was a student at the school who was expelled for disruptive behavior.

Lisa switches departments. When Lisa is kicked out of the dance department, she dramatically decides to switch tracks to acting. That wasn't something you could do at PA -- "next to impossible" is how a New Yorker Magazine article read. It quotes Laura Dean, an actual PA student who played Lisa, and who said at the time, "Of course the movie is larger than life; not everything is just as it is here...but no one wanted our school to look bad."

Classmate conflict. According to Parker, there seemed to be zero dissension amongst the students. He wrote on his website, “Considering the extraordinary social and ethnic mix, everyone seemed to get along. No one could remember a single fight or racial problem—they were probably all too occupied by their own ambitions and goals and channeled their energies into that.”

The pursuit of fame. Despite now being called “the Fame school,” those who attended back around the time of the film weren’t fame seeking. Rather, they were dedicated to craft. So much so that the school wouldn’t help and even got in the way of the movie being made about them.

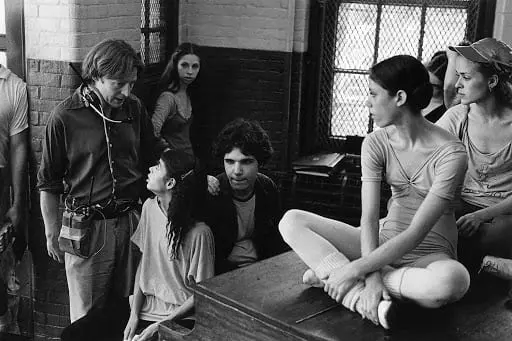

CASTING

PA students were given first shot. Parker promised the students they’d all get to audition, although he also advised he would cast a wide net for talent. He wasn’t kidding. Two-thousand kids showed up at try-outs.

The casting process took four months. In addition to the PA students, casting directors Howard Feuer and Margie Simpkin went through all the agencies. Parker said he had a wall full of Polaroids and took comfort that even if he didn’t take someone as a principal actor, he could use them as an extra.

Only one cast member was currently a student at the High School of the Performing Arts. Despite deep attempts to choose actors from the school’s pool of talent, only junior Laura Dean, who plays Lisa, was chosen from the current students. However, some of the actors who were cast were alumni and extras were mostly the school's real students.

Barry Miller had just played a pivotal role in one of the biggest hits of the 1970s. Miller had been a child actor, and had recently made an impression as John Travolta’s suicidal friend Bobby (the one on the bridge) in Saturday Night Fever. He was the son of actor-director Sidney Miller and children’s talent agent Iris Burton (she launched the careers of River Phoenix, Henry Thomas, and Kirk and Candice Cameron, among others). Miller was of Jewish descent, not a Puerto Rican Catholic.

Antonia Franceschi was currently studying at the American School of Ballet. The PA grad was tno Hilary; in fact, as a child she'd hung around with street gangs until her family directed her to dance. At 16, she was in the movie Grease (1978) as one of the dancers; she told USA Today, "I sing and dance throughout. I'm sitting behind Olivia Newton John on a bench during 'Summer Nights' with short brown hair and size-36 falsies."

Franceschi had a talent no other dancers possessed: being able to cry on cue. "They couldn't find a ballet dancer who could talk and act, too," she said. In her reads, "I did my crying scene. They threw me in with Alan Parker and I did it for the casting lady. It was a great compliment to be chosen."

Margie Simpkin found Gene Anthony Ray break dancing on the streets of Harlem. According to Parker, choreographer Louis Falco loved Ray’s raw talent. Not that he was a complete amateur – he’d won several disco dancing awards.

Gene Anthony Ray knew Leroy…and to some degree, was Leroy. Ray had been expelled from the High School of the Performing Arts for disruptive behavior (In a 2003 reunion where Ray was present, Debbie Allen said he'd slapped a teacher.) When brought in to audition for Parker, Ray quipped, “This isn’t hard for me to play. On 153rd Street and Eighth Avenue there’s nothing but Leroys.”

The violinist was actually the first person cast, in a sense. While Parker was doing research on the school, he was struck when he saw student Gennady Filiminov practicing in the stairway. The musician said it was because he liked the acoustics. Parker took a photo of him and used it as the cover image for the screenplay as they tried to sell the film.

Filiminov had a greater role that was cut, although he remained in the poster. "Alan Parker heard me playing in the stairwell, he told me about his project and had invited me for an audition....which I took and won!" Filiminov wrote to a Fame fan site. "Originally I was to have a character of a Russian Violinist (playing myself), but because the film was long as it was, several characters were cut out. You can hear me playing my violin in Fame: Sonata for violin and piano by Cesar Frank, Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto 2nd mvt. and in the final moment of the film when we are all playing in the orchestra, the film ends with my face."

Doris was supposed to be Jewish. Maureen Teefy was a year out of Julliard and had two films under her belt. However, she did have some theater school experience: she attended the Children's Theater School in Minneapolis. Parker said he was try to avoid stereotypes, and so, Doris became Irish. Teefy told USA Today, "I had no idea what I was auditioning for, Alan Parker just liked my vulnerability.

Irene Cara was the most experienced of the actors. Cara had attended a performing arts school -- one source says it was Professional Children's School, the pricey school that Doris tells the drama teacher her family can't afford, and another says it was the actual High School of the Performing Arts where she'd been accepted into all three departments. Either way, Cara told USA Today she had to drop out because she was a working actor and her family needed the income. She had been working since she was a child on "The Electric Company," a soap opera, off-Broadway and Broadway roles, and some film and TV roles. Johnny Carson even had the 12-year-old Irene on as a guest on "The Tonight Show."

Parker didn't think Irene Cara had a strong singing voice. Alan Parker said he'd seen the Puerto Rican-Cuban actress in Roots: The Next Generation and liked her frail, delicate look. Despite her having experience on Broadway in "Maggie Flynn," "Ain't Misbehavin'" and "The Wiz," working as a background singer, and playing Sparkle in the music movie Sparkle (a black musical that was a flop at the time but is now seen as a significant film), Parker wasn't sure she could sing. She sang a capella for him in person but that also didn't ring his bell. So, he asked Michael Gore to work with her. He reported back, "Boy, she's got the chops!" "Her great voice was almost a bonus as we had prepared to work with a lot less," Parker wrote on his site. "It’s fair to say that the character Coco’s unbridled ambition in our story, closely mirrored Irene’s in real life."

Lee Curreri auditioned at his school, the Manhattan School of Music. A student at the Manhattan School of Music, Curreri was recommended to the casting directors by one of his teachers, Lee Waltzer. Curreri told USA Today: "I was a musician in New York, I played piano and trombone, did arranging, accompanying and recording gigs. I had a fantastic band, and we worked on other people's records. I was even a church organist for a while. I went to Manhattan School of Music. They sent a casting agent to every music school in New York, so I auditioned there."

Curreri was dismayed that he wasn't given the role of Bruno on the spot. The actor-musician said when he went in to read for Parker, the director was holding a giant video recorder and after having him play the piano and read the sides, he put his arm around him and said, "Really excellent. Excellent work!" Curreri "naively" assumed the part was his, especially because his own story was so similar. He said he had three more callbacks after that.

In a boarding house in the Catskills, Curreri learned the part was his. He said he had a summer job working as a pianist at a Catskills resort (think Dirty Dancing). "There was this old German lady who owned the house," he said, "And, she said "Ver you expecting a part? Vell, you got it. I guess they'd called and relayed the message."

Paul McCrane brought his guitar to the audition. It was the secret sauce. McCrane grew up in Pennsylvania and was working in local theater at the age of 15. After moving to New York, he'd been in a Broadway and off-Broadway show at the time when he auditioned to play Montgomery MacNeil. Alan Parker recalled that McCrane had his guitar with him at the audition. "I asked if he’d play for me and he sung one of his own songs: “Is it OK if I call you mine”, which I included in the film — as Montgomery sits perched in his apartment window high above the flickering neon of Time Square."

Debbie Allen's role was supposed to be more significant. Allen -- arguably one of the most significant performers in the film -- is barely in it. She plays what seems to be a dance instructor during auditions who most appreciates Leroy's potential and her sidelining seems like a major missed opportunity. "I was supposed to be the nemesis for Coco," Allen told Pop Goes the Culture, "I was the senior who was supposed to be this big thing and Coco was going to show me who was the real star. But by the time Alan Parker got to my number, he already had a 10-hour movie. They let me keep the dress and told me, 'Good luck, Debbie, we know you're going to do something.' It looked like I was the teacher's assistant."

The drama teacher was PA's real drama teacher. James Moody certainly knew acting as the head of the High School of the Performing Arts' drama department. He was cast as Farrell, guiding students to dig deep throughout the film.

The class conductor was one of PA's actual music instructors. Jonathan Strasser leads his class through Mozart's "Eine kleine Nachtmuzik."

Parker wanted a real musician who'd been around the block to play Mr. Shorofsky. Albert Hague was a 25-year Broadway veteran, a composer who could play the head of the music department with real authenticity, including having no patience to indulge experimental whims. As a child of Jewish descent growing up in Germany, his family sent him to Italy to avoid the Nazis. Later, when it appeared German officers would catch up with him, he was sent to America at age 18, knowing no English and having no money. He was able to attend college and graduated with a music degree. Playing tough was no problem, Hague said at one point, "Well I grew up in a tough neighborhood - Nazi Germany."

Joanna Merlin was a casting director. Merlin had been in films and TV for decades including All That Jazz. She was more a Broadway performer and casting director for the stage. With her dancing, acting, and dealing with young performers who just don't have the chops, it's no wonder she was a fit to play Miss Berg, the I-don't-have-time-for-this dance instructor who destroys Lisa's dreams with the "you'll thank me later" speech,

Valerie Landsburg didn’t get the part. Landsburg auditioned to play Doris, but was cast in the role for the TV series.

Madonna is rumored to have auditioned.

Isaac Mizrahi is the auditioning jester. The future fashion designing icon was a student at the time. Parker took to him and, though he couldn’t find a role that fit him, but was able to work him in. Mizrahi had a puppet theater in his house so interacting with the Jester staff was natural to him.

FILMING

Parker’s British loyalty came at a cost. Parker brought over his British crew who were not union members. This caused quite a bit of controversy in the industry. However, he did managed to get his crew authorized. The exchange was that he'd hire twice as many union employees for the lesser roles, making him overstaffed -- and that was problematic. Parker didn't realize that every union employee got his own truck. The trucks alone filled the already overcrowded streets of New York.

The New York Board of Education refused to let the film shoot on any campus. The school already had too many applicants and the script indicated sex, an abortion, profanity, and drug use. Parker and Marshall met with the board and tried to assure them the film was going to be of high quality. A female board member responded, “Mr. Parker, I can’t risk you doing for New York High Schools the same thing you did for the reputations of Turkish prisons in your last film (Midnight Express).” Parker said he knew at that point, he'd lost.

MGM decided to move the production to Chicago. However, New York’s Film Commissioner Nancy Littlefield wasn’t going to let the school board prevent the city from hosting a film shoot that would bring work to New York actors and millions of outside dollars. She found two abandoned buildings Parker could transform into the school.

Alternative locations. Parker transformed two empty school buildings into his performing arts school: Haaren High at 59th and 10th and another school at 1st and 9th. The entrance to the school borrowed St. Mary’s Baptist Church, which was located directly across the street from the real PA.

Hazy shade of film. There isn’t a shot that cinematographer Michael Seresin didn’t like to filter with a foggy haze. Inspired by noir and specifically The Third Man, Seresin was said to light incense sticks to create a haze. In his other film from 1980, the former ad man turned up the sundrenched haze in Foxes – another all Brit production (Adrian Lyne would take the sublurred look and run with it).

Smoke to create "a look" was a no go in New York. While the filtered lighting was a standard style of photography in Europe, it was completely foreign to New York film industry. Alan Parker laid it out on his website:

For many years in Europe, we had used smoke in scenes to diffuse the light. Traditionally incense burners were used to puff the soft smoke into the air to catch the shafts of light, but this presented problems for some of the New York crew who were steadfastly set in their ways. Firstly, the props department and the lighting crew couldn’t agree on who was actually responsible for this new task of igniting the pellets and puffing away with the small hand-bellows before each shot. Secondly, a number of the crew (and actors) were appalled by the presence of the smoke and complained to their unions about the “noxious” working conditions. We were duly visited by representatives from the SAG and Local 644 who promptly called a halt to filming in conditions ‘possibly hazardous to their members’ health.’ We pointed out that we had been using incense on sets in England for many years, but not nearly as long as the Catholic Church who, with the exact same smoke, had according to the New York crew, apparently been asphyxiating their congregations for two millennia. Our argument was mute as SAG and Local 644 countered that they had no jurisdiction in the Vatican, but they did on a New York City film set and so the smoke was forbidden and we reluctantly abandoned the procedure in order to be allowed to continue filming.

The dancing in the streets scene almost didn't happen - two different unions and the NYPD halted production over three days. It all started when camera operator John Stanier had a personal emergency and had to return to England. Director of Photography Michael Seresin took over the role, but that's not how it works with a union.

On Day 1 of the street scene, the crew's union Local 644 shut down production. "Filming was suddenly stopped and the crew froze as a large black limousine pulled up in the middle of 46th street and out climbed a posse of union representatives, all absurdly dressed in black suits with pork-pie hats and dark glasses. (Hard to believe, but true). We were told that the DP was forbidden to operate and that we would only be allowed to continue filming if we took on an operator from their union. The alternative was that they would close us down permanently," Parker wrote. "Within an hour we had resumed filming with a cocky, captious New Yorker as replacement operator, who managed to throw spanners into every shot, impeding our momentum, but we soldiered on."

On Day 2, the New York Police Department changed the amount of hours that Parker could shoot on the street. The first day created such a traffic jam, the NYPD said that despite the approved permits the production held, they were going to reopen the streets at 4 p.m.

Then, the dancers union shut down production. Perhaps taking a cue from the crew, the dancing union leaders showed up and demanded stunt pay for the performers to dance atop taxi cabs and dance in the street. Dancers were being paid $100 a day. After Alan Marshall negotiated the additional amount and finally, the shoot was able to resume. Despite the many obstacles, the scene was concluded with eight different choreographed dances and 50 dancers on the street at one time.

The inventor of the Steadicam took over the camera operator position. Garrett Brown was the camera operator on the Oscar-winning film Rocky. He created the Steadicam technology - a platform that created smooth tracking shots which was just started to be put into use. Parker had met Brown when visiting Stanley Kubrick on the set of The Shining. Parker points to the best example of Brown's Steadicam work in the scene where Doris and Ralph are fantasizing about their future as a subway arrives.

Cameras were rolling when the cast was unaware. Irene Cara said, “Alan was very serious about being as real as possible. A lot of the scenes were filmed when we didn’t know the cameras were running so that he could capture a lot of our real, organic rapport with each other.”

The sweat was real. Shorofsky's constant dabbing of his forehead wasn't for the scene. The summer of '79 was one of the hottest on record. Shooting in old, abandoned buildings meant there was no way to cool down. Laura Dean referred to it as “the summer of no A/C.”

Lee Curreri couldn't nail the scene where Bruno's dad plays a cassette of his music. "This was the toughest scene for me because I had to be angry with someone who was playing my music in a street filled with people who were enjoying it, and it was completely against my grain," Curreri said, pointing out that he through Bruno's response was ridiculous. "I never could be mad enough. I think it's possible Alan just acquiesced to the amount of angry that I was because I think he would've wanted me to be more upset."

Barry Miller and Alan Parker clashed. Often. As a young actor with a substantial resume – having worked for nearly a decade in films and TV and as the son of a noted director – Miller’s moody behavior wasn’t channeled entirely into his character Ralph. On the Fame DVD commentary, Parker said he and Miller often disagreed on set. Miller responded, "Dear Alan, how I do miss him. A real piss-and-vinegar English bloke. We hated each other. But he made me a star, for a brief time anyway."

The cast, crew and even the director walked on eggshells around Gene Anthony Ray, and yet, felt protective of him. Ray was very similar to Leroy in many ways: he was also a street performer, he had a chip on his shoulder, and had a difficult family situation. While Ray was filming the movie, his mother was dealing drugs (during the TV show, his mother and grandmother were busted for selling heroin and cocaine). Ray had no boundaries when it came to expressing himself. Franceschi, who also came from the inner city and hung out with gangs until she found dance, described Ray as "wild" and said that Parker had a hard time containing him. Debbie Allen found that she mothered him. Irene Cara summed it up to Shondaland “He was the youngest, and believe me, he was a handful — a handful," said Irene Cara. "But we loved him, and he was a brilliant, natural actor and a phenomenal dancer."

The energy in the "Hot Lunch Jam" wasn't Hollywood magic. "The amazing thing about this scene is that when everyone starts dancing, there's this frenzy, there's this frenetic energy, which was really was happening at the time it was filmed," Lee Curreri said. "People were pushing each other out of the way to get in the camera lens. There was this competition -- this New York get-in-your-face style of dancing and performing. Alan and his director of photography managed to capture it in a beautiful way."

Doris' terrible singing as acting audition just happened naturally. "They never asked me if I sang, so it turned into an 'acting' song — it came out of the situation," Maureen Teefy said. "Sometimes good things come out of accidents."

FUN FACTS

Alt titles. While trying to come up with a title to replace the accidentally scandalous title Hot Lunch, the writers played around with “Neon Dreams,” “Spotlight,” “Break a Leg,” “Starstruck,” “Shooting Stars,” and “Pizzazz and Razzle Dazzle.”

The title was lifted from David Bowie and John Lennon. The two had a hit song a couple years earlier called "Fame." Parker said he didn’t remember it coming from that idea specifically, but thinks it could be true.

Gene Anthony Ray skipped school to audition. Ray was only 17 and was now attending Julia Richman High School – he had previously been kicked out of PA.

The Rocky Horror Picture Show scene was ripped from real life. The PA students brought Parker to a midnight screening of the cult classic, and it influenced him to include it in the film. He wrote, “I watched them re-enact the whole show, dressed as the movie’s characters — squirting water pistols in the air when it rained; answering back to the screen from an unwritten audience created script, culminating with them jumping on stage to join in the ‘Time Warp’ dance routine, with the actors on the screen flickering behind them.”

The Rocky Horror Picture Show presenter is the guy who created the concept. “We were lucky to have Sal Piro, who was the compere and main instigator/creator of the original idea of audience participation with the film,” Parker wrote on his site. “What began as a funky banter at midnight screenings — reacting vocally to kitsch lines — had developed into a full scale, highly eccentric, theatrical event. Now, everyone dressed in costume and communally blurted out their now finely honed, audience invented script.”

The students dancing on the street are actually moving to “Hot Stuff.” At the time of filming the scene where Bruno’s dad plays “Fame,” the title song wasn’t written yet. So, they subbed in the Donna Summer disco hit. Listening to the Giorgio Moroder produced song for three days inspired Michael Gore to come up with the single titled, “Fame.”

Bruno was scripted to look like a rock star. Lee Curreri said he didn’t understand the choice because Bruno “was a guy who didn’t like to be on stage, he didn’t like make a spectacle of himself.” Curreri said wardrobe would put him in flashy clothes which Parker would then reject. It happened over and over, and Curreri recounted that the wardrobe department got upset with him. “They started yelling at me that I wasn’t walking in with enough enthusiasm. Like I should bound in with a smile on my face wearing the clothes, and maybe that would help Alan accept the clothes.” In the end, the fashion department came to Curreri’s house and picked clothes out of his own wardrobe. The problem, he says, is that some of those clothes were from the back of the closet – items his mother had bought him when he was a teen. He said when he got the TV series, those clothes were shipped to LA – and so, for about a decade, he was wearing the shirts he wore when he was 13.

Just like high school cliques, subgroups did form. Paul Crane, Lee Curreri and Maureen Teefy were one pack. Franceschi, Miller, and Ray were another. Dean was also close to Ray – the two were friendly when Ray attended PA, and it developed into a friendship on set. Irene Cara had actually learned dance from Debbie Allen, and with the script including a rivalry between their characters, the two bonded further on set. Parker tended to stay away from the industry kids and spent time with the novices.

Parker disliked working with Irene Cara and Barry Miller. “Irene Cara and Barry Miller were the most difficult — Irene, because she “fluctuated” the most being more comfortable in a recording studio, and Barry because he appeared to be full of fear and hidden demons. This manifested itself in a surly, bratty awkwardness that drove the crew nuts.

The song "Hot Lunch Jam" was written as a giant collaboration with the crew and students from the school’s different disciplines. Assistant director Robert Colesberry contributed this line: “If it’s blue it must be stew, if it’s yellow, then it’s Jello.” All the collaborators get a piece of the residuals.

Lee Curreri found it hard to pretend to play his own music. He was the artist who'd recorded the music, but believed that mimicking your own music was more challenging than pretending to play someone else's music because to look authentic, he had to remember exactly what he did when he recorded it.

Parker had a wake up call that working with young adults was different than working with adults or children. “It took me a long time to realize in New York that when an actor went off to “do a line” they weren’t going over the script.

Lee Curreri had to learn to play the violin. “I had to take two weeks of violin lessons…it was excruciating! The most difficult thing I’ve ever done in music was to try and play that thing,” he said about the scene where Bruno plays the violin and gets into a argument with Shorofksy about needing to learn to play an instrument when it can be duplicated on the synthesizer. “When I had to pick up one of these things, it sounded like that! I wasn’t trying to be bad!”

The premiere was a benefit. More common in that era, the movie premiere sold seats for $150 to raise money for New York causes.

The film broke in the middle of the premiere screening event. Alan Parker recounted, "On the evening of the film’s extravagant world premiere that MGM put on at at The Dome cinema in Los Angeles, the projectionist loaded the film incorrectly, forgetting to lock the spindle. Consequently, in the middle of the ‘Hot Lunch’ number, the large reel shuffled along the spindle and fell off the projector, crashing ignominiously onto the floor. The lights went up and it took ten minutes to start the film again."

LEGACY

The title song was a winner. The title song, “Fame” won the Academy Award and a Golden Globe for Best Original Song. It also won a Grammy. It charted all over the world, including hitting No. 4 on the Billboard Hot 100 and No. 1 on the Billboard dance charts. Irene Cara sang the song constantly to the point where SNL made a parody sketch about the song ("I'll be singing this song forever!").

Other award accolades. The film brought in recognition from the filmmaking community, including six Oscar nominations in total. It won Score for Michael Gore and In addition to "Fame," it was also nominated for Original Song for Gore and his sister Lesley for "Out Here on My Own," screenwriting for only Christopher Gore (despite that massive Alan Parker rewrite), Film Editing for Gerry Hambling (one of Parker's Brits he had to fight for) and for Best Sound (so maybe those divas in the sound department deserved the respect it seems they were asking for).

Spinoffs. So many spinoffs. Fame is what you call a strong IP. A TV series was launched immediately (1982-87 that brought in $300 million in syndication) that brought back Debbie Allen, James Moody, and Albert Hague as teachers as well as Lee Curreri, Gene Anthony Ray as students. a stage musical (1988), and a remake (2009) were all spun from the success of the film.

Blink and you'll miss some of the biggest stars to come from the film were barely in it. Fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi plays “Touchstone,” the actor who auditions as a court jester. Meg Tilly was one of the background dancers. And then, there’s…

Debbie Allen was the biggest star to come from the film. At the time, Allen was a dancer, choreographer and Broadway performer who is only seen evaluating the dance auditions. She went on to have one of the lead roles in the 1982 TV series. Her combination of dancer, actress, and director helped her to sustain longevity in film and television. She is uncredited in the film.

Choreographer Louis Falco grew his work in movies, commercials, and music videos. Few choreographers make a lasting jump to on camera work. Falco collaborated with Parker again for Angel Heart (1987) as well as Bill Cosby’s Leonard Part VI (1986). He was the choreographer behind Prince’s "Kiss" music video as well as videos for The Cars and others. This is in addition to his international stage work, including choreographing for Italy’s La Scala Opera Ballet.

Songwriter Dean Pitchford went on to write and direct Footloose. He also wrote some of the early ‘80s big hits: “You Should Hear How She Talks About You” by Melissa Manchester (a PA alum!) and “Don’t Fight It” by Kenny Loggins and Steve Perry.

The ‘80s were good to several members of the cast. Below are their TV credits but many of them worked and are still working in Broadway and off-Broadway stage productions.

- Irene Cara soared in the '80s, owning a good portion of the airwaves. She sang the theme song "Flashdance...What a Feeling" for Flashdance (1983) which she co-wrote with Giorgio Moroder. She won the Best Original Song Oscar at the 1984 Academy Awards and the Best Pop Vocal Performance Grammy. The year after Fame, she was given an NBC pilot "Irene," but it wasn't picked up despite good reviews. She also starred in Body Heat opposite Burt Reynolds.

- Barry Miller co-starred with Robby Benson in The Chosen (1981) and had roles in notable films Peggy Sue Got Married (1986) and The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). He won a Tony in 1985 for his role in Neil Simon’s “Biloxi Blues.”

- Laura Dean found success as a voice-over actress, starting on "My Little Pony" in 1984. She performed on Broadway in "The Who's Tommy" and "Doonesbury" and was a dancer in the Oscar-winning musical Chicago (2002).

- Gene Anthony Ray became more famous through the Fame TV show, but struggled with personal and substance abuse issues. He continued to work in stage productions through the '80s and '90s.

- Maureen Teefy was a member of another ensemble musical, Grease 2, and played Lucy Lane in the TV series "Supergirl." She told USA Today that she'd booked an important role right after Fame, but the actor's strike prevented the production from going forward. She married director Alexander Cassini (the son of fashion designer Oleg Cassini) and they had a daughter in 1986. Teefy said at that point "life went in a different direction."

- Antonia Franceschi danced with the New York Ballet for 11 years following Fame. She continues to dance and work as a choreographer.

- Boyd Gaines had a memorable performance as Coach Brackett in Porky's (1981), playing Barbara's (Valerie Bertinelli) husband Mark in "One Day at a Time," and Jason in The Sure Thing. He continues to work in TV and film, most recently starring in The Goldfinch (2019). On Broadway, he's won three Tonys.

Paul McCrane never slowed down. McCrane said following Fame, "I got offered every sensitive and fragile role that came down the pike for a few years after." He worked in film through the '80s in movies like The Hotel New Hampshire (1984) and RoboCop (1987), he switched to series regular work in TV and hasn't stopped. His most notable TV role was as the despised Dr. Romano in ER. Currently, he's on CBS' "All Rise."

After the "Fame" TV series concluded, Curreri focused on music. He composes and works in the music departments for film and television productions.

Michael Gore and Dean Pitchford were nominated for 2019 Songwriter of the Year. Moreover, the 2020 Grammys had the biggest music stars perform their song "The Body Electric."

The school continues to give the world great performers. Timothée Chalamet, Ansel Elgort and Awkwafina are more recent graduates of what's been renamed as the Fiorello H. LaGuardia School of the Performing Arts. Alumni include Jennifer Aniston, Morena Baccarin, Azealia Banks, Corbin Bleu, Diahann Caroll, Michael Che, Keith David, Dom DeLuise, Omar Epps, Eartha Kitt, Nicki Minaj, Sarah Paulson, Suzanne Pleshette, Helen Slater, Wesley Snipes, Lesley Anne Warren, and Billy Dee Williams. Another graduate was Sarah Michelle Gellar, who married Freddie Prinze Jr., the son of Freddie Prinze.

The film inspired an explosion in performing arts high schools across the globe. What was a novelty in New York at the time found quick expansion with the demand of kids who wanted to attend programs with a speciality in the arts. Most of America's largest cities including Los Angeles and Houston have a performing arts high school and similar schools can be found in countries all over the world, including Istanbul. Lee Curreri said, "People who were at just the right age when the movie and the show came out saw this and went, ‘Wow! This is it. This idea is calling me. This show is calling me.’”

Several of the dancers became significant players in the entertainment industry. Debbie Allen highlighted some of the performers you may not have even realized were in the 1980 film. "Michael DeLorenzo ('New York Undercover'), who was a dancer in the movie, went on to have a much bigger part on the show. Louis Venosta was a principal dancer and he became a screenwriter (Bird on a Wire and The Last Dragon). I went on to direct and co-produce 'A Different World.' There was a lot of young talent in that ensemble. It was a glorious experience.”

Steadicam is now used as an industry standard. The invention from the man who was brought in as a mid-shoot replacement went on to achieve critical acclaim, including from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Garrett Brown continued to innovate and currently holds 50 patents in camera technology.

Hundreds of thousands or even millions of people were inspired by the film. The casts of the movie and the subsequent TV show will tell you they have heard the stories from performers who said they were moved to action by the film. Antonia Franceschi said, "I have people come up and say, 'I started dancing because of you.'"

Montgomery helped gay men feel more accepted. McCrane shared with USA Today, "A fair number of people, especially gay men, tell me the film and the character were important for them, because at the time there weren't openly gay characters on screen." Erica Gimpel, who played Coco in the TV show ,said even though Montgomery was never identified as gay in the series, men shared with her how meaningful the movie character was to them. "“Fans all over the world tell me stories about being gay young men who were terrified to come out...and they say, ‘You don’t know how much this show saved my life.’ Or ‘I didn’t feel accepted. This show made me feel accepted.’”

WHERE ARE THEY NOW?

AIDS took the lives of several key members of the Fame family. The new disease ravaged the entertainment community in the '80s.

- Screenwriter Christopher Gore died from AIDS in 1988. He’d written several episodes of the TV series. He died in Santa Monica at the age of 43. At the time, his mother reported the cause was cancer.

- Choreographer Louis Falco passed away from AIDS-related complications in 1993. He was 50.

- Gene Anthony Ray lived hard with a raging drug habit and contracted AIDS in the ‘90s. He struggled with his health and complications from a stroke ultimately took the dancer’s life in 2003. He was 41.

Other Fame cast members who passed: Albert Hague (Mr. Shorofsky) in 2001, Anne Meara (Mrs. Sherwood, also the mother of Ben Stiller) in 2015.

"Bruno" and "Mr. Shorofsky" had a lasting relationship. "He was my mentor. I would bring him my songs to critique. He was an old-school composer," Lee Curreri said about his relationship with Albert Hague. "I miss him." Curreri and Hague lived in the same small Los Angeles beach town.

Paul McCrane is an in-demand episodic TV director. McCrane still acts and has worked as a series regular since the '90s. But in the last decade, his resume as a director has grown significantly. He's helmed several episodes on shows like "Chicago Fire," "Chicago P.D.," "Empire," "Star," and "Scandal."

Maureen Teefy is exploring the LA Theater scene. Teefy had a one woman show and in March 2020 was in a play with another '80s notable, Michael Pare, that played at the Sherman Oaks Whitefire Theater. Teefy lives in Venice, Ca., and it appears decided to get back into theater after a divorce and at the point when her daughter Isabella was grown.

Lee Curreri married Laura Dean's sister. Curreri married Sherry Dean in 2000. The couple have two children.

Lee Curreri continues to do it all to fill in entertainment's music needs. Curreri has an "urban beach studio" in his Marina del Rey home. He composes, produces, arranges, and performs -- he calls himself "a musical Swiss Army knife."

Ironically, Barry Miller grew to despise fame. While it’s clear he holds dear his role and involvement with the film, Miller became sickened by what the pursuit of fame had become. In 2009, he publicly stated he would abandon pursuits that would keep him in the public eye, stating to USA Today, “I wish to have no further shelf life in the public sphere. I wish quite sincerely to be forgotten."

Soundtrack

RSO Records, the label behind the successful soundtracks of Saturday Night Fever and Grease, released the motion picture soundtrack to Fame on May 16, 1980,- the same day as the film was put into limited release across the nation. Two singles were released, both performed by Irene Cara: "Fame" which reached No. 4 on the Billboard Hot 100 and stayed on the charts for 16 weeks, and "Out Here on My Own" which peaked at No. 16. The soundtrack reached No. 7 on the Billboard 200.

"Dressing Room Piano" by Michael Gore

Director: Alan Parker

Screenwriter: Christopher Gore (Alan Parker, uncredited)

Release Date: May 16, 1980

Rating: R

Opening Weekend Rank: The film did a slow rollout, starting in limited release in only three theaters.

Opening Weekend Box Office: $188,000 (in three theaters)

Lifetime Gross: $42 million

Budget: $8.5 million

Production Company: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Distributor: United Artists